Alright, let’s get back to business, shall we?

How does this go again? Excuse me if I take a moment to get my bearings. The last time I was writing on this subject, the very flames of hell were licking at my monitor from outside my lone apartment window. Now they have been replaced with the icicles of the holy fanfiction of one Dante Allighieri. No, but we have in fact had a rather mild winter this year, no snow down here in the Green River valley, though it is a little chilly tonight. It will… not quite freeze, reaching a mere 33 degrees.

But enough about the weather, let us move on to today’s subject.

Summary

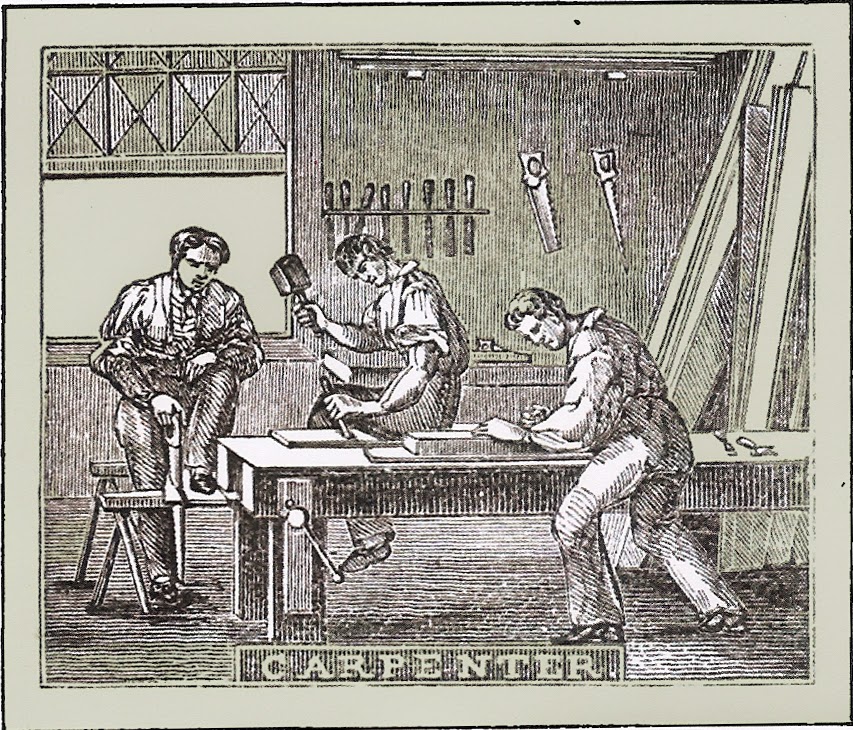

Ishmael describes the carpenter of the Pequod, who is an extremely stolid and reliable man, capable of accomplishing just about anything required of him, whether it relates to his ostensible profession or not. His bench is always set up on the deck of the ship, except when they are actively processing a whale.

Through his many years, the carpenter has acquired a singular personality: he will do whatever is asked of him quickly and efficiently, and gab the entire time about something unrelated. He is a kind of human Swiss Army knife*, simply pulling out different functionality from his brain as the situation demands, with no consideration or seemingly any thought at all.

Analysis

Oh man, this is a great chapter to come back to. Short and sweet, but with a lot of meat on the bones, both in terms of context and in terms of deeper thematic meaning. This is one of many of the crew of the Pequod who seem to be entirely allegorical characters… but could also just be, like, some guy that Melville met during his years at sea. It’s hard to say, as the truth is probably some combination of the two.

Multum in Parvo

First things first: let me swing back around to that asterisk I inserted in the summary.

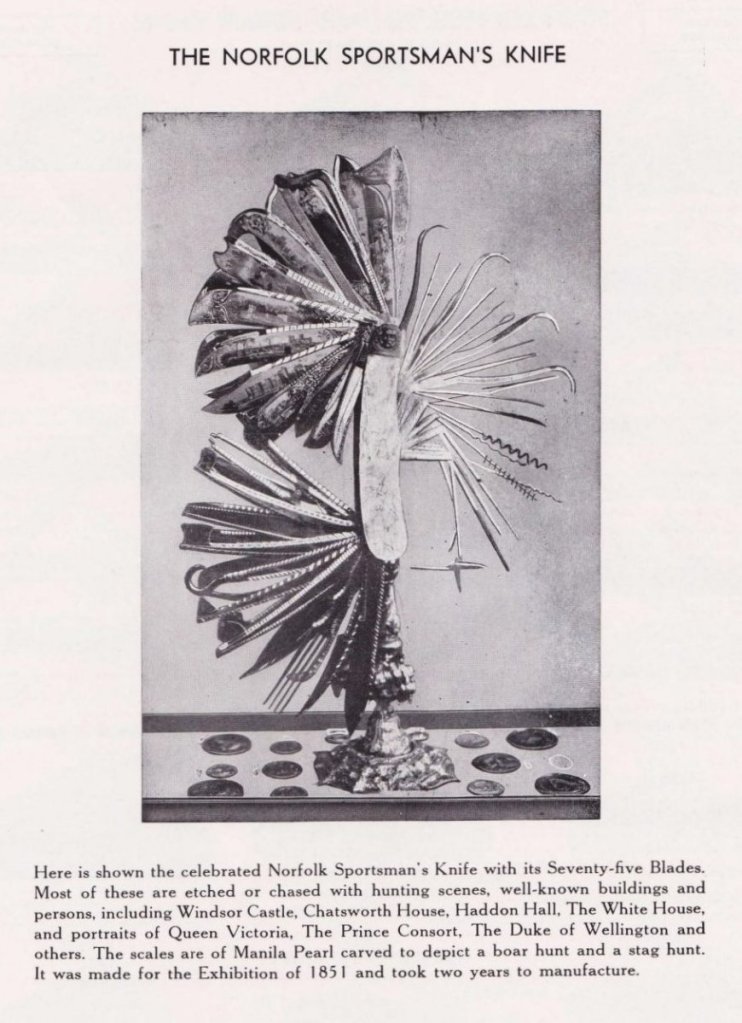

*: The Swiss Army had not yet adopted the use of their famous eponymous knife at this point in history. That wouldn’t happen for another 30 years, some times in the 1880s. Ishmael instead refers to a “Sheffield contrivance”, like so:

He was like one of those unreasoning but still highly useful, multum in parvo, Sheffield contrivances, assuming the exterior—though a little swelled—of a common pocket knife;

Just a fun little bit of business, apparently these sorts of multi-tools were a big thing in the early 1850s. As mass mechanical reproduction became more of a common thing, it was easier for such magnificent creations to make their way into the hands of regular people. Or, well, at least a slightly lower rung of society than before.

Sheffield was, and is still, of course, a manufacturer of such things. I myself had a Sheffield pocket knife for many years, belonging to my grandfather. The spring was broken, so it was fun to play with, and still useful for opening recalcitrant packages.

I will note that this is one of those times where my attempts to research this specific subject brought me back many references to this exact passage. Always kind of funny, I do forget that this book is massively influential, and puzzled over by many scholars over the years. Most of the images in this post were taken this wonderful thread on the All About Pocket Knives forum, posted just last year, on this very subject. Does my heart good to see such places thriving in this modern age.

A Practical Man

Now that the fun facts are out of the way, let’s get into the true business at hand: so is this dude supposed to be Jesus?

I’m only half kidding, but of course when a character is introduced as a carpenter (or a shepherd (or a fisherman)) one must immediately suspect that some manner of biblical allegory is at play. Biblical references are of course never far from the pen of our old friend Ishmael (just look at his own self-appointed name), but this seems like a case where it’s a bit more… pointed.

I think that, in this particular case, it is a very interesting and perhaps wildly heretical take on the figure of Jesus, one that aligns with some of my own beliefs or at least vague notions.

So, the carpenter. He is stolid, utterly reliable and omni-capable. He will do whatever it asked for him, no matter what it is, or who asks it.

[…]; he was moreover unhesitatingly expert in all manner of conflicting aptitudes, both useful and capricious.

There is a universality both in the nature of his talents and how they are applied. There are no tricks or gotchas, there is no need for argument, there is no need to convince him of anything. He simply sits down and does the thing that needs doing. All he asks is that you listen to him while he does it (which we’ll get to in the next chapter).

The Great Dodge

So how, then, are we to map this stolid, useful man to one Jesus Christ?

Well, I think it follows in a rather straightforward manner. There is no hell, there is only universal salvation. He is for everyone, everywhere, for every purpose, to solve a problem. And that problem is perhaps the most fascinating bit.

It’s a vision of Jesus as the ultimate scapegoat. He died for our sins, period. That’s the end of that story. It’s finished. What do you do about an vengeful and capricious god? Well, you find a loophole and defang him. What if he could relate to us? What if he could come down and see us, and therefore forgive of everything, forever?

That last paragraph probably contained about fifteen heresies, but you see what I’m saying. Heresies, traditionally, are often borne of common understanding of complicated religious and philosophical issues. My own approach is to take these things somewhat simply, and not really worry about dogma too much. That’s what I learned in my church, after all.

Thus, Jesus is a humble carpenter. Here to accomplish something, impart some wisdom, and be done with it. No pomp and circumstance, no need for great arguments, no flash and spectacle. Simply sit down at your bench and fix what is broken.

Dualistic Homunculus

There’s one last thing I want to make special note of, in the final paragraph of this chapter:

Yet, as previously hinted, this omnitooled, open-and-shut carpenter, was, after all, no mere machine of an automaton. If he did not have a common soul in him, he had a subtle something that somehow anomalously did its duty. What that was, whether essence of quicksilver, or a few drops of hartshorn, there is no telling. But there it was; and there it had abided for now some sixty years or more.

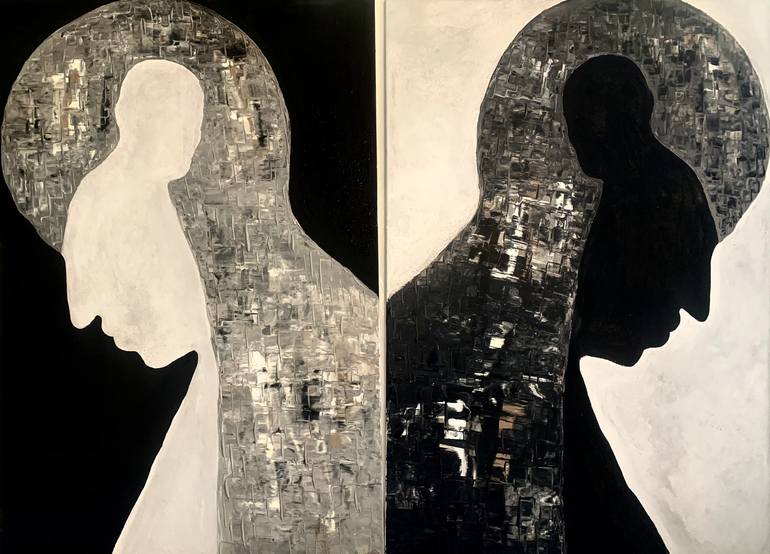

This is the thing that really caught my attention, and brought me back to this very direct biblical allegory. There is a disconnect between the carpenter’s affect and his inner soul. He seems flat and practical, but while he is accomplishing his mundane tasks, he rattles off nonstop. Naturally, this also brings to mind the idea of a mundane human body with some sort of divine spark within.

There is a theory of mind called dualism, of which the basic gist is that there is a separation between The Mind and The Body, as completely separate entities. Essentially, your body is a big machine that is being controlled by a little man in your head. You may have seen this general idea expressed in cartoons, it’s another one of those very fun and easily graspable philosophical concepts.

Now, there are many implications of this, which we don’t need to get way into right at this very moment. Suffice it to say, there are some advantages and disadvantages to taking this view of ones own self. Personally, I find it a bit reductive, and not particularly realistic with relation to my own experiences.

No, the self is found in every part of the self. Your body, your brain, your gut bacteria; how others see you, how you perceive yourself as 2am on a cold and rainy winter night. It’s all you! There is no strict separation, how could there be?

At every level, it is composed and composes elements of a complex and interrelated systems, going up and down. You are thirsty, that affects your mood, which affects your thoughts, affects your feelings, affects your emotions, affects your memories, affects your physical actions in the moment and into the future. Breaking it down does disservice to the marvellous complexity of the world.

Uff da fee tah, that was a fun one. I think I have a good routine down now, I’m going to read the chapter one night, either a Sunday or Monday, and then ruminate on it, and then actually write the post by Wednesday of that same week. I do miss being able to do my reading and take copious notes while sitting outside at the Pike Place Market… but alas, my job is more demanding these days. At least I get to be inside, though it’s sometimes not much warmer.

And hey, I got into some philosophical stuff that wasn’t about capitalism this time! That’s a fun change of pace, haha. I’m sure it’ll come back around again, it always does.

Until next time, shipmates!

LEt’s GOOOOOOOO. He’s back

LikeLiked by 1 person

Are you back? Finally! I am still catching up on your Moby Dick writings, chp 72 to be exact, but I’m a bit worried going on by myself.. Thank you for your talented writtings!!

LikeLike

“Uff da fee tah” was an expression I’d never read nor heard ere stumbling across your blog! I had to google it: It turns out it’s some expression among Americans of Scandinavian heritage; A sort of comradely in-joke or equivalent of oy vey. Initially, it baffled me, but delighted me greatly when I, a Swede myself (that is, native of the country) realised that it’s a distortion of “uff då, fy då.” What a quaint little relic—we don’t say it in the motherland anymore!

Americans know that their expansive land is a great tapestry of varied diasporas and heritages (about which opinions vary, sadly), but few perhaps know how very antiquated many of these cultures are! The Amish are the obvious example, but as a rule, all languages spoken by any American diaspora will have changed little from the time this diaspora themselves arrived there, and the smaller the diaspora, the lesser the change. Indeed, even U.S. English itself, is not exempt from this. Particularly its southern dialects have been more phonetically conservative than even the King’s English! An Alabaman speaks more like the Queen of Shakespeare’s time than the late Queen of our day!

I take it you’re might be of Scandinavian heritage yourself then, eh? Perhaps a Minnesotan? I know it’s there where the most of the million Swedish emigrees settled (which makes sense; the environment would’ve been similar.) They were as many as the Irish, but did, for some reason, never get the same hold on U.S. culture that Irish got. They got St. Patrick’s day (a bizarre tradition anyway, in that it’s so global!) where my distant kinsmen have to contend with that—all things considered still very delightful and honouring—Uff da fee tah!

P.S.: I’ll end with this: if anyw US-Scandinavian would want to scandinavize their vocabulary with a substitute to Uff da, I’d recommend you start saying uschianemej, (ush-EE-anuhmay) quite a mouthful, that means the same thing. It’s said by Goofy in the translations of the older Donald Duck comics, which I’ve understood are much more popular in Europe than in America. Goofy himself is there known as Janne Långben, lit. “Johnny Longleg” for some reason. The other names are equally distant from their English names, but this will have to be a topic for another time…

LikeLike