You’ll never guess what this chapter is about!

Ah, sometimes this book can get a bit repetitive. But it can be hard to tell if that’s the book’s fault, or mine for reading it so many times. I would say that Moby Dick is a kind of… mixed masterpiece. It is not a sort of perfect clockwork thing, where every spring and cog fits together in some flawless and immaculate design. No, it’s more of a great pile of ideas, rudely shaped into something transcendent. Here is another piece, for your perusal.

SUMMARY

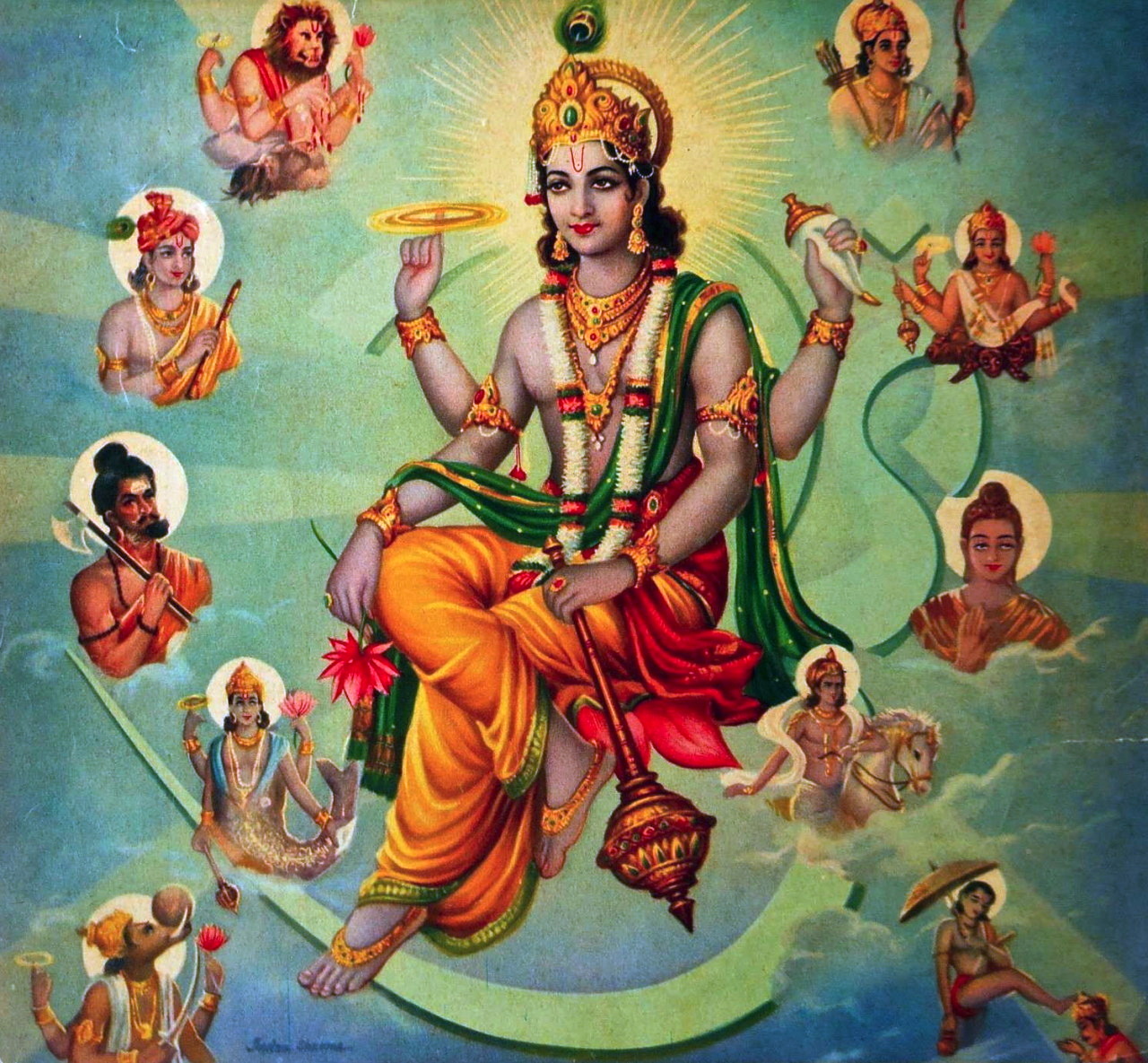

Ishmael runs down the list of the great historical and mythological figures that he counts among the Brotherhood of Whalers. He includes both figures who were involved in actually fighting whales, like the vaunted Perseus of Greece, and Peter Coffin of Nantucket, as well as those who have been swallowed by or transformed into whales, such as Jonah and Vishnu. He purports that both Hercules and St George ought to count, since the monsters they fought were probably actually whales, those being the only beasts massive and strong enough to really count. Anyway, Ezekiel calls a whale a “dragon of the sea” in the bible, so any reference to a dragon could be interpreted as a whale.

How about that, huh! Whalers seem pretty great now, eh?

Glorifying a Dirty Job

The purpose of this chapter, I think, is twofold, both aimed at improving the reputation of whaling. This is a theme we’ve seen a lot in this book, and at this point it feels like a major point of inspiration for Melville in this whole enterprise.

As in the previous chapter where he drew a connection between the British crown and whaling, the main point of connection here is to simply reflect the glory of existing popular heroes onto this maligned profession. If he cannot win over the audience by portraying the peril of the act itself, the bravery of practitioners, then he will reach for these kinds of distant connections.

It’s funny to think that the reputation of whalers has actually only gotten worse as the profession has receded into our own mythological past, even as this very book is esteemed as a piece of great art. All of this glorification falls on deaf ears in a modern age where all butchery is despised, but especially of those great leviathans that we now understand to be a precious and limited resource.

Ishmael really ends up reaching to make some of these connections, often in a pretty fun way, that almost feels like it’s making fun of sophists:

[…]; so Vishnoo became incarnate in a whale, and sounding down in him to the uttermost depths, rescued the sacred volumes. Was not this Vishnoo a whaleman, then? even as a man who rides a horse is called a horseman?

Gilding the Lily

Really, it all goes back to Ishmael attempting to get across just how big and scary sperm whales are. The kind of a thing normal people never have to deal with, something that can really only be approached in concept through mythology.

And yet, it is also hilariously overblown. Taking every mythological sea monster, and even some monsters that didn’t live in the sea, and saying they must be whales, so all these heroes count as whalers.

[…]; and considering that the animal ridden by St. George might have been only a large seal, or sea-horse; bearing all this in mind, it will not appear altogether incompatible with the sacred legend and the ancientest draughts of the scene, to hold this so-called dragon no other than the great Leviathan himself.

It’s the same sort of reputational chest-puffing as the dunking on Old Europe stuff in the last chapter, really. Picking and choosing things to make your case that you’re good and cool, actually. Going to any lengths to draw connections that not only make you look, but like the best that there is.

It’s the kind of thing that really only works if you’re preaching to the choir, Ishmael is writing for his whaling buddies, not for an actual audience of ignorant landsmen. The tone here isn’t actually persuasive, it’s more just puffing up a thing that you already know by rolling off examples of its greatness.

The Tragedy Of It All

Hidden within this trumped-up hagiography of whaling as a profession is a hint of the not-so-secret tragedy of this book. The thing hiding in the background, which has already been revealed in bits and pieces, by implication: Everyone except Ishmael dies in this voyage.

The bitterness present here, and other places where the wretched reputation of whaling is described and argued against, is relating to the personal tragedy which Ishmael is still grappling with. What do these deaths mean, if they weren’t heroic and great, in a historical or mythological sense?

This book, in macro, is representative of Old Ishmael’s personal struggle over the tragedy which he experienced firsthand. Was this just the random cruelty of nature? Or was there some deeper meaning to it? Some grand design, some cosmic order that was being disturbed, some divine justice being served?

Even here, in this smug, funny little chapter, where he puffs his chest and rolls off the names of saints and heroes, there is a hint of that bitterness. If not heroes, then why did they die so tragically? This must be an epic tale, there is no other reason for it to end the way that it did.

And so, his bitter work is to backfill the mythology. To build this ordinary fishing voyage into the stuff of gods, a battle of wills between devils and angels behind the scenes. The thing that makes it interesting, though, is that Ishmael himself is not convinced. He lets his doubts leak in all over the place.

These chapters, then, are more about convincing himself that these things are true, than addressing the audience. In the fictional world of Moby-Dick; or, the Whale, I’m not even sure if these writings were ever published. A single copy or two may sit on a shelf in some dingy whaler’s tavern, but otherwise, it is merely an act of therapeutic catharsis for one Ishmael.

Ah, that was a fun one. I’m really enjoying the challenge of writing these in a more readable style, with headings and smaller paragraphs and whatnot. I already tend not to like overly long paragraphs, and this is giving me a good excuse to write even more efficiently.

We’re moving into another section of non-narrative chapters, so there will be lots of opportunities for more analysis of Old Ishmael. My thesis about this book changes slightly over time, but I keep finding more and more evidence for it, which is very satisfying. Maybe I’ll compile it into a proper academic paper once this project is finished.

Until next time, shipmates!