Ahhh, I had a nice vacation, of sorts. Really, I was just dog- and housesitting, I never got much further than a mile from my house, but I was away from my computer, and thus could not continue this blog. But it’s good to be back! And for a nice big, round number, no less.

This chapter is a good one. I actually took notes on it before my vacation, and to dig them out again to refresh my memory. As you’d guess, it’s dealing with some of the fallout from the revelation of Ahab’s secret stowaway crew and personal whaling boat, as well as digging into some themes that I’ve really been ruminating on over my summer break.

SUMMARY: Stubb is amazed that Ahab hunted a whale from a boat in his condition, but Flask tells him that it’s reasonable given that he didn’t lose his whole leg, only up to the knee. Ishmael then discusses how Ahab was seen secretly preparing the spare whaling boat for his own use, in retrospect. His stowaway crew integrate themselves into the general crew very easily, whaling ships take all kinds and they’re not too different. But the harpooneer, Fedallah, keeps himself apart and remains a mystery to the end.

So, a bit of a subdued reaction, in the end.

Ahab had a secret crew of stowaways, and secretly prepared a boat for his own personal use, customizing it with a hole in which to brace his ivory leg, as he has on the quarter-deck. But, it’s not really a big deal. Like, sure, it’s dangerous, and it takes someone with wild abandon to actually go out on a hunt in those conditions, but hey, it’s dangerous for everyone!

Considering that with two legs man is but a hobbling wight in all times of danger; considering that the pursuit of whales is always under great and extraordinary difficulties; that every individual moment, indeed, then comprises a peril; under these circumstances is it wise for any maimed man to enter a whale-boat in the hunt? As a general thing, the joint-owners of the Pequod must have plainly thought not.

Really, Ahab only had to work in secret because of a) his own personal sense of drama and b) the owners of the boat would never allow it. Now that they are well out at sea, and he has the crew under his spell, he can be open about his intentions and his action alike. Who’s gonna stop him? Certainly not his first mate, we know that already, and the others are either happy to go along or indifferent.

You may think that suddenly having more crew members appear out of nowhere would be more troubling, but that’s also no big deal in the world of whaling. Working, as they do, out in the middle of nowhere, they often come across castaways and vagabonds and add them to the rolls. Remember, this is exactly how Queequeg first left his island home: he jumped onto a whaling ship and refused to leave. Instead of being locked up, they just put him to work as a regular crewman.

Now, with the subordinate phantoms, what wonder remained soon waned away; for in a whaler wonders soon wane.

When you’re out in the middle of the ocean, manpower is at a premium. You’re gonna take all you can get, and considering the makeup of the existing crew, these wild Filipino hands won’t really stand out too much, despite the gusto with which they were first introduced.

However, Fedallah is different. He stands apart from everyone, constantly shadowing Ahab, whispering in his ear, ever mysterious and shrouded in darkness both literal and metaphorical. He’s an interesting character, the way he’s kind of singled out as especially strange even in this chapter. It’s never revealed how he came to attach himself to Ahab in particular, or even what sort of relationship they truly share. We are just to chalk it up to another occulted mystery, along with the silver calabash and the skirmish afore the altar in Santa.

There are a lot of different things to talk about with regards to Fedallah, and his whole Deal. He’s designed to be shrouded in mystery, subject to the most intense orientalism you’re likely to find in fiction anywhere. The very platonic ideal of a shadowy figure from The East, with all the various implications that go along with that. Just get a load of this quote, from the end of this chapter:

But one cannot sustain an indifferent air concerning Fedallah. He was such a creature as civilized, domestic people in the temperate zone only see in their dreams, and that but dimly; but the like of whom now and then glide among the unchanging Asiatic communities, especially the Oriental isles to the east of the continent—those insulated, immemorial, unalterable countries, which even in these modern days still preserve much of the ghostly aboriginalness of earth’s primal generations, when the memory of the first man was a distinct recollection, and all men his descendants, unknowing whence he came, eyed each other as real phantoms, and asked of the sun and the moon why they were created and to what end; when though, according to Genesis, the angels indeed consorted with the daughters of men, the devils also, add the uncanonical Rabbins, indulged in mundane amours.

He all but says that he’s not even human! Some sort of Nephilim lost to history, but reemerging to shepherd Ahab’s doomed quest for supernatural vengeance. Something beyond even the cannibal savagery of Queequeg and his people, so far outside the limits of “civilized” people that it could only be something weird and supernatural.

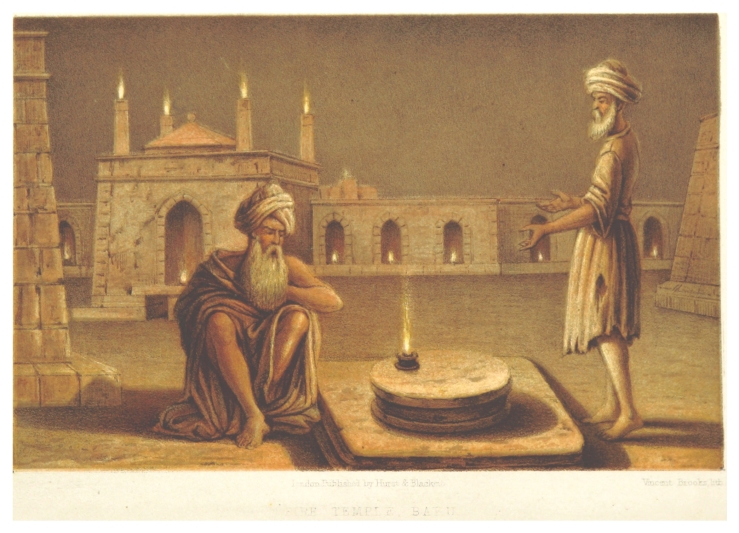

Fedallah is, ultimately, mostly just a prop to make Ahab all the more grand and mysterious himself. This description, along with some future bits from the text, bring to mind an enormous subject that I’ve been ruminating on for a while. You see, Fedallah is a Parsi, often referred to in this book as a “fire worshiper”, and is shown to have real supernatural powers.

There’s, like… an interesting dynamic in the way that christianity (and Abrahamic faiths in general) treat the supernatural in relation to themselves and other religious traditions. The difference between “magic” and “a miracle”, so to speak. The shifting extent to which an object of worship is expected to produce results, or whether that is necessary at all.

I’m getting ahead of myself. Like I said, it’s a big subject, and I’m certain I’m reinventing one wheel or another here, I’m not really a scholar on this subject the same way that I am on certain kinds of philosophy. Let’s go through it more slowly.

Often, in stories, so-called “pagan” religions (which is to say those that are not part of the whole Abrahamic tradition which encompasses Judaism, Christianity, and Islam) are treated both as if they have a real connection to some sort of supernatural force, and yet that is also used as an indication that they are somehow invalid or inherently evil. Either the supernatural force is not truly divine in some sense (ie it’s actually a demon or whatever) or it turns out to be totally fake. Think of a cult sacrificing someone to a god that turns out to be either a demon or just a big animal, like King Kong.

This trope goes way, way back, but it has changed over time. In the book of Daniel, which is really a collection of extremely old folk tales, Daniel demonstrates repeatedly that his god is actually real, and causes real miracles, while the Babylonian gods are totally fake. In one story, a god is supposedly eating a bunch of food every night, but it turns out to just be the priests sneaking in and eating it.

So, the notion of what “faith” even is has shifted radically over time. It used to be that it was merely believing that your god/religion/traditions were real, worked, and had effects in the world (got results, so to speak), while others were completely wrong. Now, that is not even considered enough, because it’s too high of a mark to hit when information is so easily shared across wider distances both physically and in time.

Argh, I’m getting lost in the weeds. What I mean to say is: It used to be enough to get results, and say that your god was real. Now, faith requires something beyond that, a deeper commitment to an idea rather than a belief about physical realities that could possibly be disproven. In order to make it more durable, religious faith had to be abstracted.

So, you can say that these supernatural occurrences that you hear or see are either just the bad kind of supernatural stuff, or that they don’t prove anything! In fact, that it is more virtuous to believe without having to see results, rather than believing what you see before your eyes.

It lets you have it both ways, essentially. It brings to mind, as many things do, this passage from Umberto Eco’s essay Eternal Fascism: Fourteen Ways of Looking at a Blackshirt:

When I was a boy I was taught to think of Englishmen as the five-meal people. They ate more frequently than the poor but sober Italians. Jews are rich and help each other through a secret web of mutual assistance. However, the followers of Ur-Fascism must also be convinced that they can overwhelm the enemies. Thus, by a continuous shifting of rhetorical focus, the enemies are at the same time too strong and too weak. Fascist governments are condemned to lose wars because they are constitutionally incapable of objectively evaluating the force of the enemy.

It’s a very effective strategy, making your enemy seem both powerful and weak at the same time. It’s only a strategy that works in abstract ideas, as Eco says, but when we’re talking about religion that’s the only arena that matters!

There’s a whole thing here about how pagan religions are treated by horror movies… the fact that Fedallah is a parsi… the way that he’s compared directly a devil… Martin Luther and sola fide… it’s just a lot. I may revisit this whole thing the next time Fedallah comes up, or just spin it off into its own article.

Man, it’s amazing to me that I haven’t inserted that Eco quote before, I think about it constantly. It’s another one of those things where once you know about it, you can’t help but spot it all over the place. Especially in right-wing rhetoric, it goes without saying.

Ahh, nice to get back into the swing of things with a wild tangent taking up most of a post. The next chapter will probably give me more to chew on that’s directly relevant. Pretty sure it’s about whales.

Until next time, shipmates!