Y’know, I’m starting to have more sympathy for Ahab.

I, too, feel like cursing the sun, and never looking skyward again, as it beats down and boils the air around me. That is to say: it’s getting hot again, and I hate it. Supposed to get above 90 for the next few days, and I will be melting into a puddle, so we’d better get into this chapter before that happens.

Summary

The Pequod is caught in a sudden typhoon. The sails are immediately torn apart, while the sailors desperately try to preserve the whaling boats, which are precariously lashed to the side of the ship. Alas, despite this, Ahab’s whaling boat is smashes against the side of the ship, leaving a large hole right where he usually stands.

Starbuck and Stubb are on the quarter-deck directing their efforts. Stubb is as jolly and detached as ever, singing a song in the middle of the gale, while Starbuck yells at him, trying to get him to stop and take things more seriously. He attempts to draw a direct line between Ahab’s recent action and this calamitous turn of events, predicting certain doom if they continue, but Stubb ignores him.

Ahab comes on deck. Seeing lightning in the distance, Starbuck tells the men to throw the ends of the lightning rods overboard, chains that direct the power of the storm hamlessly into the sea from the top of the masts. Suddenly, three great gouts of silent flame appear on top of all three masts. As the mysterious St Elmo’s fire wraps more and more of the ship’s rigging, the crew fall silent, watching the flames. The three harpooneers appear more terrifying than ever in the eerie light.

With Fedallah’s assistance, Ahab grabs hold of the chain connecting the mainmast’s lightning rod to the water, in order to feel the power flowing through it. He then gives a monologue in which he declares his fealty only to that power. In the midst of this monologue, the flames atop the masts suddenly triple in size.

At the end of the speech, Starbuck draws Ahab’s attention to his harpoon, now unsheathed and sitting in the front of his now-ruined boat. It is now affected by the strange phenomenon, shooting out two great gouts of pale flame from its barb. Starbuck takes this as a sign of Ahab’s evil, and the doom he brings upon them all. He calls upon the crew to join him in mutiny and turn the ship back towards the safe harbor of Nantucket, away from certain death.

The whalers begin to follow Starbuck’s orders, but Ahab grabs the flaming harpoon, terrifying them into submission. He reminds them all of the oath they swore, which is just as binding as his own: to hunt the white whale, or die trying. He then extinguishes the flame on his harpoon, as the other men flee in terror.

Analysis

It has been a while since we had a chapter this long and involved. Really putting my summarizing skills to the test here. I was tempted to elaborate more on some of the details… but no, that’s what this part is for.

This is another insanely cinematic scene, which I don’t think was included in any of the adaptations. Well, I guess you couldn’t exactly do something like this with special effects in the ’50s, huh. I really think you could only adapt this book with animation, and this chapter is a perfect example of why. There are big things going on here, and in order to properly visualize it, you’d have to get abstract to some degree.

Alas, it’ll never happen. Moby Dick is a serious work of literature, so in the west it can never be done in a serious manner with animation. Animation is a genre, and it’s for children. Still, even in this modern age, where many understand on some intellectual level that it can be so much more, in the popular consciousness it is still consigned to kids stuff.

The Pale Fire

So, let’s talk about this fire.

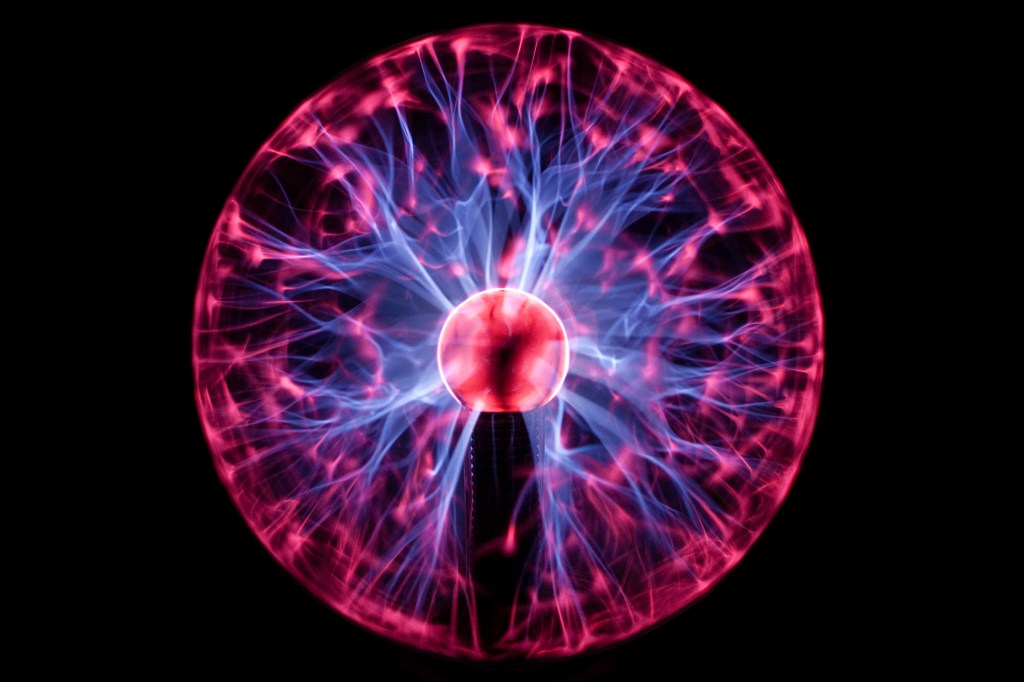

It’s not actually fire, per se, but rather plasma, aka the same stuff lightning is made of. This is a real phenomenon, when specific atmospheric conditions are met, which is well understood now by scientists, but which I will not delve too deeply into. Suffice it to say: it happens when it’s stormy, and specifically when there’s lightning going on nearby.

It can appear on all sorts of things, but is most famous for showing up on ships. Generally, it isn’t dangerous, except as a prelude to a lightning strike. It is actually taken as a good omen by sailors, as a flame that doesn’t consume it seems miraculous, thus its connection with St Erasmus (aka Elmo), the patron saint of that profession.

So, what the sailors in this chapter are seeing is not like big gouts of actual flame. It’s more like electricity, in the form in which it can be “seen” at all. Imagine that, but in the open air, and you’ve never seen electricity in a contained environment before in your life. You too would find it mysterious and perhaps supernatural.

Weather phenomena like this, in the context of a story like this, are a place where the seemingly supernatural can actually intercede in real-life events. It sort of levels the playing field, there is no expertise around this stuff, people just have to respond however they think best. It’s pure superstition, given physical form.

Which is to say: it’s not that you know it’s supernatural. It’s that nobody knows what’s going on with it. Maybe it is, maybe it isn’t, but there’s an unapproachable uncertainty there, a gap of knowledge of the world.

As a side note, Herman Melville was fascinated with lightning, and wrote a short story about a lightning rod salesman. There was a lot of interest in it in the 19th century, in general. Figuring out what was going on with electricity, people made all sorts of wild claims. Not just the St Elmo’s fire, but the whole range of electrical phenomena were a space of uncanniness and potential “magic” made real. Something to keep in mind with this chapter, in this modern age when it is considered less mysterious.

Omens and Portents

We get three distinct perspectives on the mysterious flames in this chapter: Stubb’s, Starbuck’s, and Ahab’s, in that order.

Stubb sees the fire in the rigging in a very straightforward way: it’s the will of god! Or, rather, it’s the spirits of the dead, come to pass judgment on the ship. He begs for their mercy, that the ship not be destroyed. He’s not making any specific claims about their meaning, it’s just a force outside of his control, which he cannot affect in any meaningful way.

They are held in the hand of some gigantic force, which could easily reduce the entire ship to splinters and kill every man dead. What can you do in the face of that besides laugh and sing? There’s no use in anything else, may as well have fun with it.

Starbuck, meanwhile, sees this whole event as a direct result of the ship going along with Ahab’s doomed quest. His blasphemy has brought this fate upon them all, and they need only turn their back on the hunt for Moby Dick in order to be saved.

It’s a very American view of salvation, even up to this present day. It doesn’t matter what you’ve done in the past, salvation is always possible. Just stay on the straight and narrow! It is possible to know what god wants you to do, all you have to do is follow these rules. Looking upon the strange and wondrous and saying “ah yes, I was right all along!”

And then we have Ahab. What does he see, when he looks up on the mysterious plasma lights, wiggling about along the rigging and atop the masts? He sees only what his eyes tell him: a great and mysterious power. One that, perhaps, he could use to his own ends.

Unaspected Power

Let’s dig into this monologue a little bit, which is made while Ahab is essentially holding a live wire, connecting the storm above to the ocean below. As he says, matching its fire with his blood.

This speech is wild as hell, and one of the most fascinating things in this book. What we have here is Ahab working through his relationship with the powers of the natural world. Literally negotiating with them, laying down an ultimatum, and receiving an answer right then and there, at least in his mind.

First, he identifies the power he is communicating with:

Oh! thou clear spirit of clear fire, whom on these seas I as Persian once did worship, till in the sacramental act so burned by thee, that to this hour I bear the scar; I now know thee, thou clear spirit, and I now know that thy right worship is defiance.

Ahab has felt the lash of this power before. It is not specifically the lightning, but the vast powers of the natural world in general which he is turning his attention to. Not personified in divinity, in spite of his naming it as a spirit, but as it exists: a force that moves in the world, without purpose or meaning.

No fearless fool now fronts thee. I own thy speechless, placeless power; but to the last gasp of my earthquake life will dispute its unconditional, unintegral mastery in me. In the midst of the personified impersonal, a personality stands here.

He asserts his own individuality in the face of this mass of unmotivated power. He declares that he will sieze this power for himself, even if it blinds or kills him. Those are the stakes, which he accepts without complaint.

And thus the ultimatum: if he opens his eyes and can still see, if the lightning passes through him without harm, then it is his ally forever. This is the real heart of it: Ahab is not simply defying the forces of nature to kill him or save him, he is saying that his cause is the same as that natural force.

Oh, thou foundling fire, thou hermit immemorial, thou too hast thy incommunicable riddle, thy unparticipated grief. Here again with haughty agony, I read my sire. Leap! leap up, and lick the sky! I leap with thee; I burn with thee; would fain be welded with thee; defyingly I worship thee!

This bit reminds me a lot of the Thomas Pynchon book V., which had a lot of weird stuff about the nature of objects. The unknown and unfathomably bleak and blank existence of things that have no will of their own, nothing to retreat to, no motive to move themselves in one way or another. Melville is exploring the same ideas here.

Think about it: the lightning exists for a second, born of natural forces, and then is gone forever. Who mourns it? Who takes notice of its sad fate? Who could possibly have sympathy for a thing with no feeling, no history, no future?

Ahab, that’s who. He himself is but a mote in the great whirling maelstrom of life, a thunderbolt streaking across the sky, just like his epithet, Old Thunder. An old thunderbolt is all of a few fractions of a second in age, by their relative lifespan. And yet, it carries such destructive power that it may strike terror into the hearts of those creatures which live ten million times as long.

The Great Unbreachable Veil

This is such a big, vague idea that you could connect it to all sorts of things. I find it fun to interpret it in a very literal way, which is the path that leads to Bram Stoker and HP Lovecraft, and the modern tradition of cosmic horror. These vast, unknowable forces that actually control the movements of the world. We are their playthings and they don’t even care.

The terror, there, is both physical and philosophical. The realization of great and terrible truths, and also a scary monster that’s gonna get ya. In this case, electricity is our Cthulhu. But instead of malice or even indifference, Ahab imagines an inherent blankness, a space waiting to be filled up by the passions of humanity. The role of man is to give voice to that voiceless suffering.\

You could just as easily read this as a big analogy about slavery. Ahab is breaching the gap between White and Black, finding a sympathy with the great mass that provides and yet is kept apart. Remember, since this is before the civil war, this is always on the mind of literally every American citizen.

Or, in a similar vein, you could take the anticapitalist reading. This great senseless power is the workers, human beings who are abstracted by their economic system into an unthinking force, to be bought and sold on a market. He will be the great man who takes up their cause and strikes a blow against those who would use them, etc etc.

One can read all sorts of things from this, as long as you can tell the right sort of story. Grasping hold of a great power through sympathy… and the wielding it, in service of a doomed quest.

Ahab Holds It Together

Oh yes, we shouldn’t forget the end of this chapter. Starbuck basically shoots his shot, calling on the crew to turn the ship around and head for home. The conflict that has been simmering finally comes to a boil! But then, it is immediately resolved, when Ahab does indeed take up the power of the storm, his own harpoon wreathed in pale flames, simply brandishing it about in a basic threat of violence to get his way.

This is a real turning point for Ahab. He’s done considering his options, he’s fully committed now. He’s abandoned his faith entirely, and found a new power to replace god in his personal life: nature itself. And not as an object of worship, but as a willing partner in his scheme, helping him finally achieve his end.

After all, Ahab doesn’t want someone who he has to negotiate with. He doesn’t want a back-and-forth, he wants someone who stands as an equal, but does not speak. Who exists to be used without complaint, as it has no will of its own.

The reason Ahab feels such sympathy for the storm is that he too was taken up and used by a power far beyond himself: Moby Dick. It turned its tail and smashed his boat, then opened its jaw and rended his limb from his body. Then just swam away, finished with him. This moment of abject supplication has scarred Ahab forever, in more ways than one.

So it comes to this: him holding lightning in his hands and saying “either kill me or join me as a collaborator”.

Man, I think this is one of those chapters you could write an entire book about. There’s so much that is built out of this, so much that goes into it. It is a crucible of a tremendous amount of literary output, a dynamo that still runs large parts of modern culture.

The human ability to relate to inanimate things is truly boundless, and I find that wonderful.

Until nex time, shipmates!

This is a great chapter and I think Melville is stirring up 2-3 previous noted experiences of St. Elmo’s Fire. HMS Ship Bounty with Captain Bligh, HMS Beagle with Charles Darwin, and Richard Henry Dana in 2 Years Before The Mast, all comment of this common event.

Capt Bligh, is overthrown. But not Ahab. Darwin notes the event without further discussion. Dana’s discussion is much closer to Melville’s.

My suspicion here is that Melville is using the storm like Shakespeare. Foreboding and the symbolic soul of Ahab. But I think it is also a reference to the 1850, Fire Eaters of the Southern Politicians. Fire Eaters are so committed to slavery that they will leave the union.

LikeLiked by 2 people