Ahhh, finally feeling better.

My cough is finally clearing up. I can breathe freely for the first time in like three weeks. I was starting to go a bit stir-crazy, being cooped up in my apartment this whole time. Man, I don’t think I could handle working purely from home, I gotta get back into the office.

Summary

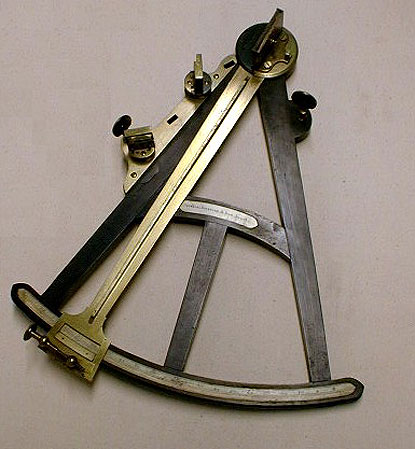

Ahab uses his quadrant to take a reading of the sun at noon, and thus determine the precise longitudinal position of the Pequod. Then, he throws in on the deck and stomps it to splinters with his feet, because it will not tell him anything about the future, only the present, and he doesn’t want to rely on the sun for information anymore. He will only rely on things that do not require consulting the heavens: the ship’s compass and dead reckoning at the horizon, along with the log and line.

The crew looks on somewhat alarmed, especially Starbuck. Stubb, however, is impressed and amused, as always.

Analysis

Well, looks like I was dead-on in my last post, huh. Ahab is continuing down in his spiral of madness. Or, rather, continuing in the line of thinking from the previous chapter, which is causing him to act in ways that are more and more disordered.

Tightening His Grip

Much like Hamlet, the thing going on here is simultaneously a descent into madness, and yet also very logical. We get to follow along with Ahab’s thought process, from the last chapter into this one, and see why he would do something that seems so inexplicable to the rest of the crew.

Before, Ahab saw a whale turning towards the sun, in some last symbolic gesture towards a love of warmth, some gesture of fealty to the heavens. At least, that is how he understood it, as a sort of prototypical or animal religion, a respect towards the thing that gave it life, its origins, even though that thing would not help in its current condition.

Now, as he goes through the usual routine of taking a reading on his quadrant, he suddenly realizes that he’s doing the same thing. He’s being a damn hypocrite. All of this fancy knowledge doesn’t actually help him one bit in his current goal, his only goal in life!

Foolish toy! babies’ plaything of haughty Admirals, and Commodores, and Captains; the world brags of thee, of thy cunning and might; but what after all canst thou do, but tell the poor, pitiful point, where thou thyself happenest to be on this wide planet, and the hand that holds thee: no! not one jot more!

What does the quadrant do? Well, it tells him exactly where he is, right now, on the globe, even if he’s in the middle of the featureless ocean. But to what end? He doesn’t need to know that. He needs to know where Moby Dick is!

So, in the same way that he has spurned further gams with other whalers, unless they have useful intelligence, he will have no truck with useless instruments that refuse to tell him what he wants to know. Indeed, all of this fancy knowledge of the ways of the world are useless to him, unless they can give him knowledge of his quarry.

And then he realizes that the quadrants takes readings of the sun, and it’s really over:

Science! Curse thee, thou vain toy; and cursed be all the things that cast man’s eyes aloft to that heaven, whose live vividness but scorches him, as these old eyes are even now scorched with thy light, O sun! Level by nature to this earth’s horizon are the glances of man’s eyes; not shot from the crown of his head, as if God had meant him to gaze on his firmament. Curse thee, thou quadrant!

Looking up towards the sun, in supplication to some higher power, is now so anathema that he will not even use astronomical instruments to calculate his position on the ocean.

It’s actually surprisingly logical: killing Moby Dick is a purely a purely symbolic act, so it must be undertaken in a properly symbolic manner. If he rejects god in pursuit of his metaphysical vengeance, why would he metaphysically rely on god to help him in his quest?

Essentially: if he’s really gonna do this, he’s gonna do it right, or there was no point in the first place.

Off the Rails

At the same time, this is Ahab beginning to slip. As he descends into a more solipsistic view of his quest, he is starting to risk more and more alienating his crew, and thus inciting a mutiny. Everyone was gathered ’round to watch the captain take his regular reading from the quadrant. And then he just… throws it down and starts yelling at it.

They’re bought into the idea of killing a particular whale, because why not? They’re sympathetic, in the abstract, to their captain’s plight and mad quest. But they’re not really taking it seriously as a problem until it starts to manifest in these ways.

Starbuck is, naturally, the most deeply concerned:

“I have sat before the dense coal fire and watched it all aglow, full of its tormented flaming life; and I have seen it wane at last, down, down, to dumbest dust. Old man of oceans! of all this fiery life of thine, what will at length remain but one little heap of ashes!”

He sees the situation very differently, not merely in its practical aspects. While the common whaler may be concerned about their captain acting a bit odd, Starbuck is chiefly concerned with his fellow man’s eternal soul!

What he sees, accurately, is Ahab abandoning everything in pursuit of his mission. From Starbuck’s perspective, this is foolish, as nothing actually matters except faith in god. All of these earthly matters, revenge and justice and whatnot, are nothing compared to the eternal life of the soul. Just a heap of useless dust, at the end of the day.

Starbuck doesn’t think that Ahab can’t or shouldn’t kill Moby Dick, but rather that his all-consuming quest to do so is damning him to hell for all eternity. It is a fruitless gesture, metaphyscially meaningless, no matter how much significance is heaped upon it. In this way, Starbuck, the man of faith, takes on the role of the chief skeptic of the Pequod!

I’m fond of the phrase “you cannot logic someone out of something they didn’t logic themselves into”. If someone is acting on faith, or deep emotion, you can’t change their mind by pointing out the logical fallacies they’re making. Unfortunately, we are in the opposite situation here, where Ahab has logic’d himself into madness, but Starbuck will only use emotional and religious appeals to try and pull him out.

Everything’s Fine

And then, we have Stubb, the ever calm and collected second mate. This isn’t his first rodeo, and he knew what he was signing up for.

“Aye,” cried Stubb, “but sea-coal ashes—mind ye that, Mr. Starbuck—sea-coal, not your common charcoal. Well, well; I heard Ahab mutter, ‘Here some one thrusts these cards into these old hands of mine; swears that I must play them, and no others.’ And damn me, Ahab, but thou actest right; live in the game, and die in it!”

Sometimes, you go to sea, and find out your captain is a bit cracked in the head. That’s his prerogative! He’s the captain, he’s gonna do things his own way, and the rest of the crew has the privilege and being along for the ride.

The thing that’s impressive about Ahab is how well he’s playing the hand life has dealt him. He managed to keep it together well enough to make it this far in their voyage. He hasn’t completely lost his mind, at least not yet.

Stubb has that critical ironic distance from the action, to be able to judge it as funny no matter how real and close the danger may be. In this way, he’s similar to the reader of this book, looking at these events from the safety of a different plane of reality.

So what if Ahab’s tormented? If his boat sinks? If he’s consigned to the flames of perdition forever? It’s no skin off our nose. It’s merely interesting, diverting, to see the process happen.

Hell yeah, I love it when I find myself on the right track. I suppose it ought to come as no surprise, given that I’ve read this book before, but never so closely, of course.

So much of my time is taken up engaging with, well… not to put too fine a point on it, but dumb nerd shit. I love it, and I love playing around in those universes, taking things too seriously, treating them like little clockwork universes that must abide by their own logic, coming up with hypotheticals. That sort of thing.

But it’s nice, at the end of the day, to come back to a nice, deep, thematically rich and dense piece of proper literature. Like, oh, yeah, there’s so much meaning baked in here, you can cut it with a knife. It actually stands up to tremendous amounts of scrutiny. I only got here by drilling down through the layers of stuff on top, of course. Too often I find myself drilling down the same way, and just finding nothing, or at least nothing interesting.

Until next time, shipmates!

Robin –

Well, I am caught up with you now; I just wanted to say how much I’ve enjoyed your commentary on the book as I’ve made my way through for the first time. I stumbled across this around chapter 8, and ended up coming back to it every 5-10 chapters to see your thoughts. Thanks for all the work here – they have been great and thoughtful reflections, with a lot of insight but also a lot of personal input and perspective that make it deeply valuable. It’s the kind of thing I tell my students – what you bring to a text can be as important as what’s there, and your personal reactions are equally valuable as anything anyone else has.

Thank you so much for these – I look forward to the next ones (though I fear I will pass you before then!)

PS – did I miss you ever doing a big post on Pentiment? Man, I loved that game.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! I’m so glad you enjoyed it.

I never did write the Pentiment post… I still want to, though. It’s a real masterp- err, magnum opus (New Vegas is their masterpiece :P).

LikeLiked by 1 person