The pieces are starting to fall into place.

It’s funny, so much of this book is either vague and philosophical, blowing out its themes to a vast scope, or extremely mundane and specific, that one quite forgets that there’s an actual plot going on, and certain things must be set up for it to conclude. Not that we’re ever going to fully get away from Ishmael’s philosophical reveries, of course. Yet, this is one such chapter, containing a pivotal development that will resonate with the inevitable end of this tale.

Summary

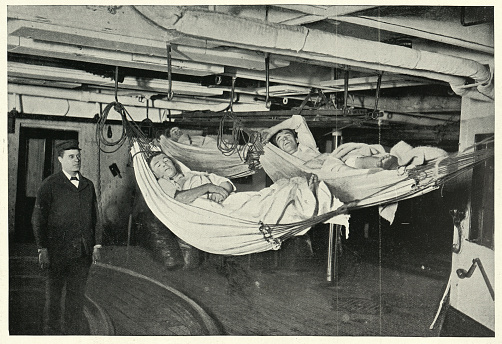

While working on opening up the Pequod‘s hull to find the leaking cask, Queequeg falls ill. As a harpooneer, he has a major role in the operation, down in the bowels of the ship, and has little opportunity to rest and recover until he is fully unable to work.

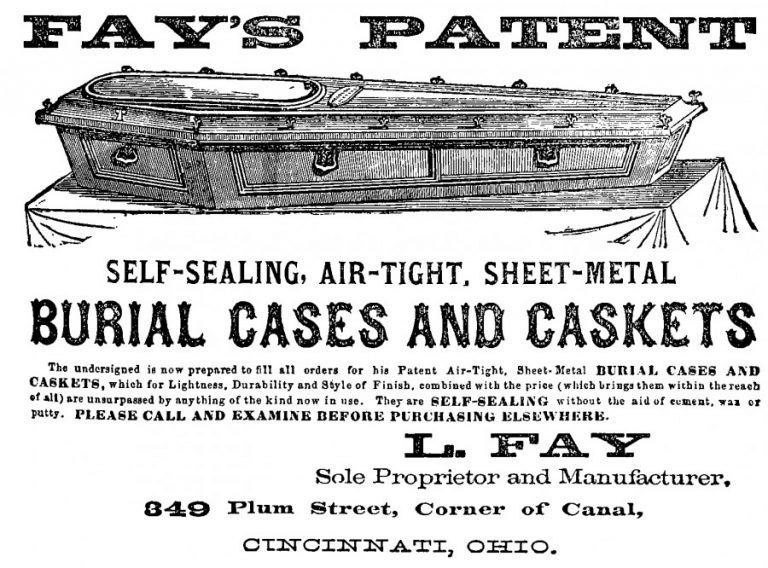

Convalescing in his hammock, Queequeg has but one request: that he be set adrift in a proper coffin at sea, like the ones he saw at the church in New Bedford, rather than the traditional method (tossed overboard wrapped up in his hammock). This wish is related to the ship’s carpenter, who immediately sets to work crafting a coffin from some spare wood he had laying around, taking Queequeg’s measurements with his usual stolid attitude.

Queequeg prepares the coffin with many earthly comforts, and then tests it out by actually climbing inside of it. Pip mourns Queequeg in his coffin. After being satisfied with the coffin, Queequeg decides he doesn’t want to die after all, and then rallies and quickly recovers from his illness, eating enormous meals to revive his former strength. The coffin he takes on as a footlocker, keeping his belongings in it, and carving a copy of his tattoos on its lid… which, incidentally, are the work of a mysteirous prophet of his tribe, and supposedly describe a complete theory of heaven and Earth, though nobody has ever been able to decipher it.

Analysis

Hey remember Queequeg? Ishmael’s husband? Well, he’s back to nearly die and then recover in the same chapter. Feels almost jarring to have two chapters with actual events occurring on the ship, back to back no less!

The Old Married Couple

There’s a fun thread in this chapter that’s easy to miss, I think.

Ishmael is still harboring intense feeling for Queequeg, both at the time that he was sick in the past, and at the present when he’s writing this book. And why not? They were married after all.

We have been denied ground-level interactions between Ishmael and his dear husband for many, many chapters now. The vast majority of the book takes a thousand-foot view, or focuses is on other characters in ones and twos, not our original deuteragonists (like a protagonist, but there’s two of ’em). Perhaps this is because it is too painful for Old Ishmael, the author of this book, to recall their time together.

I do not think he would describe the wasting away of, say, Stubb in these specific terms:

But as all else in him thinned, and his cheek-bones grew sharper, his eyes, nevertheless, seemed growing fuller and fuller; they became of a strange softness of lustre; and mildly but deeply looked out at you there from his sickness, a wondrous testimony to that immortal health in him which could not die, or be weakened.

[…]

So that—let us say it again—no dying Chaldee or Greek had higher and holier thoughts than those, whose mysterious shades you saw creeping over the face of poor Queequeg, as he quietly lay in his swaying hammock, and the rolling sea seemed gently rocking him to his final rest, and the ocean’s invisible flood-tide lifted him higher and higher towards his destined heaven.

Not to bust out an old saw, but there is simply no heterosexual explanation for this.

This, along with some later details like a translation of Queequeg’s words, make it 100% clear that Ishmael was sitting at his husband’s bedside for the duration of his illness. What true devotion! What sweet and tender love between men drawn together by circumstance.

You know, it’s easy to make jokes about sailors falling into homosexual habits during long voyages at sea, but when you get down to it there’s something sweet about men coming to care deeply for each other. Also, the story of Ishmael and Queequeg could be read as something of a subversion of that idea, since they became married not after long months of isolation, cramped together on a boat, but after knowing each other for less than 48 hours, on land.

This is not a relationship born out of base desperation, but rather a pure and mutual love and appreciation.

Anyway, let’s talk about that old specter of all American fiction: racism.

The Beloved Savage

There’s a lotta noble savage bullshit in this chapter. It sucks and is annoying.

Like… Ishmael, and by extension Melville, clearly appreciate and love specifically people indigenous to the South Pacific. But, he cannot fucking help himself with this shit. Part of it is of course just part of being a man in mid-19th century America. Even the most staunch abolitionists were saying things that would get them canceled on twitter back then.

There is this fundamental tension where recognition of the joy of multicultural exchange and appreciation for a foreign culture rams headfirst into ideological racism. The belief that they must be different in some fundamental way, perhaps even a different species. Things work different for them in a biological level, their minds are foreign, etc etc.

One could be exceedingly generous and couch all of those things in more modern terminology, say that Melville is simply lacking in vocabulary to express his ideas, but I don’t think that’s really fair. At the end of the day, Ishmael kind of talks about Queequeg like he’s a dog, where you’re just sort of guessing at its thoughts and feelings. Anthropomorphizing a fellow human being, rather than simply communicating with them. Disgusting.

Grand Unified Theory

One of the most striking things in this chapter is this bit right in the last paragraph where we learn the meaning of Queequeg’s tattoos, kind of:

And this tattooing had been the work of a departed prophet and seer of his island, who, by those hieroglyphic marks, had written out on his body a complete theory of the heavens and the earth, and a mystical treatise on the art of attaining truth; so that Queequeg in his own proper person was a riddle to unfold; a wondrous work in one volume;

In the modern, common understanding, a prophet is strictly someone who sees the future, so it may seem strange that they would write some sort of metaphysical theory rather than, well, a prophecy. But, in fact, a prophet is traditionally someone who is able to communicate with God, and those communications often but not always concerned future events.

Ultimately, perhaps this is Ishmael’s view of his savage friend: a marvelous mystery to be solved. His greatest regret! That he could not explore that relationship and truly understand the love of his life on a deep and true level.

Anyway, in a more literal sense, it’s very interesting that these are not normal tattoos, though it does fit with the idea of Queequeg basically being island royalty that we got ages and ages ago.

Theology Through Obscurity

There are a couple bits of common Christian mythology at play here as well, one of which ties into the whole noble savage idea. The first is that the actual cosmology of the universe is a divine mystery. What’s the actual workings of Heaven and how does it interact with Earth and perhaps Hell? Well, literally only God knows. There are lots of theories, which are adopted as common beliefs, but really in the end nobody knows.

This rhetorical technique of appealing to a grand mystery is very common in Christian theology, especially among protestant denominations. Many of the founding ideas of the religion lie in uncertainty, after all. “No one knows the hour” of Christ’s return, and whatnot.

The other thing going on is related: the idea that magic is real, but only practiced by nonbelievers. You see this all the time in modern horror movies, where the magic will be some ancient Sumerian or otherwise pagan deity. That witch is casting real spells! But don’t take that as an indication that her belief system true, no no, far from it. Rather: it is more important to have faith in that which cannot be proven, rather than that which can. I feel like I’ve written about this before, but it’s been a while, so I’ll leave it in.

The interesting thing here is that there’s no indication in this chapter that the prophecy of Queequeg’s skin is in any way inaccurate or to be denigrated. It is not connected to an evil, occult religion of pagans, but rather simply taken as the work of a true prophet, a small divine mystery, and its inevitable loss is a tragedy.

I suppose that in the 19th century, there was something of a more ecumenical craze, seeking foreign philosophies that were available to Western European intellectuals for the first time. This is, of course, one of the cornerstones of orientalism, that the mysterious East is replete with true magic and unknown wonders, etc etc.

So, this is an expression of that same fundamental tension of the noble savage stereotype. The yearning for something exotic and strange, but also a desire to keep it at arm’s length, to keep it strange, as that is what you truly value about it. Ishmael is picking at this idea, but cannot find his way through… in time.

[…]; and these mysteries were therefore destined in the end to moulder away with the living parchment whereon they were inscribed, and so be unsolved to the last.

Man, there was a lot going on in this chapter, but it ended up being more thematically coherent than I thought it would be. And I didn’t even really get into the actual coffin itself!

Ah well, I’m sure that coffin will never come up again, certainly not at some critical moment that changes the fate of any important characters.

Until next time, shipmates!