Summer continues apace here in Pacific Northwest, and it has been awful, here in my little apartment.

This place was not designed to deal with this sort of heat. I get the radiant warmth from lower floors, so it is nearly impossible to maintain livable conditions without sitting directly in front of a fan at all times. And, over the past weekend, we had some awful wildfire smoke to boot! Ugh. The rains of fall cannot come soon enough.

Summary

Ishmael circles back around to remind us of the meeting between the Pequod and the Samuel Enderby (of London), where Ahab abruptly departed that foreign vessel and fairly leaped back onto his boat and then upon the deck of his own ship. These violent actions jolted and strained his ivory leg, and he became worried that it might break.

This issue of maintaining his leg only served to fuel Ahab’s hatred of the white whale, as he saw this current anxiety as the child of his part torments. Indeed, he had come to the conclusion that while positive and negative emotions can give birth to others of their same kind, there is also a possibility of joy leading to nearly infinite sorrow in the long run, so it must win out in the final accounting.

Now, this was a well-founded fear, as Ahab had apparently suffered such a break in the interval on land between his last fateful voyage and this one, in an accident that left him quite injured for many weeks. His circle of friends kept it a closely-guarded secret, but Ishmael was able to suss it out somehow (he does not reveal how he knows it now).

Not wishing to repeat this misadventure, Ahab quickly summons the ship’s carpenter and orders him to make a brand new leg, from the ivory they have collected on the voyage thus far. He also orders the blacksmith to pull out the forge once more, and assist in any way that he can.

Analysis’

This is a very interesting chapter, feels as if it has its feet in two modes at the same time, serving as a transition from non-narrative back to narrative prose, as well as operating in two aesthetics that are common in this book.

Poetical Legalese

That is to say, it is a combination of the kind of overly-precise-to-the-point-of-comedy language that Ishmael often employs when describing historical events or matters of recorded fact, with the elevated, shakespearean language of his more philosophical reveries.

Nor, at the time, had it failed to enter his monomaniac mind, that all the anguish of that then present suffering was but the direct issue of a former woe; and he too plainly seemed to see, that as the most poisonous reptile of the marsh perpetuates his kind as inevitably as the sweetest songster of the grove; so, equally with every felicity, all miserable events do naturally beget their like. Yea, more than equally, thought Ahab; since both the ancestry and posterity of Grief go further than the ancestry and posterity of Joy.

There is a real tendency, as I’ve mentioned before, when reading books from the 19th century to sort of… glaze over bits like this. Like, oh, he’s just going off about something and repeating himself again, let me scan down and see where things move on to another topic. But there is really something to be gained from zeroing in on a passage like this and thinking about what’s going on here.

We are getting a combination of off-the-cuff poetic language, talking about sorrows begating one another and poisonous reptiles, with a kind of legalistic clarity. He goes on, essentially, to make a clear argument about these sorrows and joys, and set it out in the form of a closing argument before moving on to the actual action of this chapter.

Personally, I really like it! It shows the way that Melville is playing around with tone in this book, using the form of words to direct the impression of the reader. Defying the usual genre tropes of the day, and of this day. All of this is treated with appreciation from the remove of time, it’s clearly the voice of Old Ishmael poring over his notes and recollections, and yet it contains a kind of immediacy of emotion.

Ishmael desperately wants us to understand Ahab, as he himself wishes that he could. He is laying out his case based on the events which he knows to be true, and his argument takes the form of poetry.

The Origin of Sorrow

Now, as to the substance of this argument of Ishmael’s, I found it fascinating. Every time he touches on religion in a deeper way, he really gets as some interesting ideas that wouldn’t expect to see in a book of this vintage.

This is the main passage that stuck out to me, essentially the thesis:

To trail the genealogies of these high mortal miseries, carries us at last among the sourceless primogenitures of the gods; so that, in the face of all the glad, hay-making suns, and soft cymballing, round harvest-moons, we must needs give in to this: that the gods themselves are not for ever glad. The ineffaceable, sad birth-mark in the brow of man, is but the stamp of sorrow in the signers.

Essentially making a theodicy, from Ahab’s perspective. It’s not that God allows these things to happen, that’s missing the point. The nature of sorrow and joy is that they self-replicate. Therefore, the creators of the world must also have had their sorrows, which were then percolated into their creation, as coffee into boiling water.

The reference to multiple “gods” gives this a clear pagan-ish slant, but I think it is an interesting argument from a Christian perspective as well. The perfection of God is such that he must not withhold things from his creation.

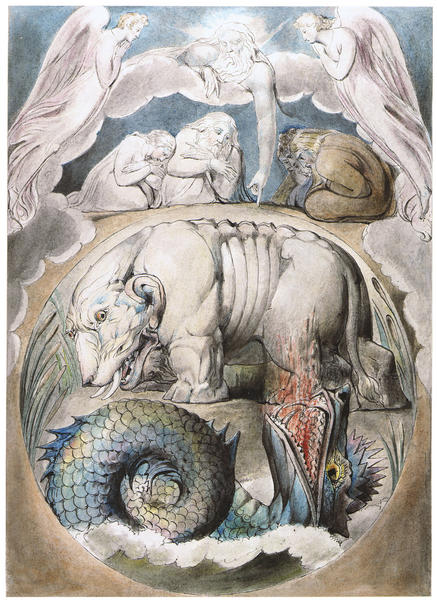

In one sense, it’s just the ol’ Job dodge again (I made the hippo, what do you know, etc), but from a different angle. There are whole mechanical operations of the full picture of existence that we can only guess at based on bare bits of evidence we can collect from our own experiences.

Is this not the very essence of human existence, and indeed of all scientific pursuit? I suppose this chapter doesn’t presume to explain anything at all in that greater sphere, just present some evidence for our consideration.

Ahab’s Hidden Sorrows

In the same way, Ishmael can only present the stray bits of evidence for Ahab’s hidden sorrows, since he himself had no access to his captain’s mind, nor his inner circle of friends and family. He treats the old man like he has the same mysterious depths and unknown yet unarguable reasons behind his actions as God.

That direful mishap was at the bottom of his temporary recluseness. And not only this, but to that ever-contracting, dropping circle ashore, who, for any reason, possessed the privilege of a less banned approach to him; to that timid circle the above hinted casualty—remaining, as it did, moodily unaccounted for by Ahab—invested itself with terrors, not entirely underived from the land of spirits and of wails.

Ahab was increasingly isolated, which was why nobody really knew about it on the Pequod, and he was a sailor, so he invested this accident with an extra bit of superstitious terror, as is his wont.

Perhaps this incident is the thing that really sent him off on his monomania, not even the initial loss of his leg. Not merely this great suffering, but the idea that this suffering was now part of his life forever, multiplying itself in more incidences and repetitions of the same trauma over and over. The only way out was to strike back against that which had injured him: fate itself.

And this is why he orders a whole new leg be constructed just because he feels nervous about the old one.

Oh yeah, we’re gettin’ into a good part now. Those last few chaptes really dragged a bit, but this is a really fascinating little arc, about the replacement of the leg. As we draw closer to the inevitable end of this tale, the focus of the narrative with return more and more to our curséd captain.

Since my kindle finally broke completely earlier this year, I decided to pick up another copy of this book, for easier referece and reading. I was shocked to discover how close to the end we now are! There are still so many important things to come, I suppose they are all stacked together here towards the final act. Though this book does defy easy structures like that, of course.

Until next time, shipmates!

been reading your posts for I while as I embark on my first reading of Moby Dick. They’ve been very useful. I hope I can read more of them!

LikeLike

? Where are the rest of the chapters brother man?!?

LikeLiked by 1 person

As a junior in high school who is being forced to read this mammoth of a book… I cannot thank you enough. I’ve read through this entire blog, and it’s really made me appreciate this book to a whole other extent. I’ve genuinely enjoyed these past 3 excruciating weeks due to the fantastic and humorous insight you possess. That being said, I am so incredibly upset that its ended here. Hope to see another post soon:)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear Robin:

I came across this blog while reading Moby Dick for the second time, in preparation for seeing this performance later this month (I’m including this link in case this theatrical version ever comes your way: https://artsemerson.org/events/moby-dick/

I was about halfway through the book when I found your blog. I just love it! You provide great information and insight, but it so immediate and non-academic. I love how you love Moby Dick, and Melville! So many people, when I have told them I am re-reading Moby Dick, have seemed to remember reading it as having been a chore, but like you I find it both humorous and deeply, soul-searchingly thought-provoking.

I look forward to you continuing this project when the time is right for you!

In the meantime, I’ll read the posts from the first half of the book!

Be well, Shipmate!

LikeLiked by 1 person