Guhh, it’s hot.

The one bad thing about living in this apartment, rather than at my parents’ place in West Seattle, is that it gets hotter and stays hot longer. We always had a nice breeze coming off the water, but now I’m inland! A who two or three miles from the Salish Sea, probably! Merely on a river valley… alas! Anyway, I’ll go turn my fan on and we can get to the business at hand.

Summary

Old Ishmael wants to start talking more about the bones of the sperm whale, but first he feels the need to explain how he came by this knowledge in the first place. After all, it’s not like you can pull a live sperm whale onto the deck of a ship! They always dump the bones down into the depths of the ocean, only keepint the head and the blubber.

Well, whalers do occasionally pull whole whale cubs onto the deck, where they are killed and butchered. He has learned quite a bit about the inner workings from these acts, but he has also had an opportunity to explore the preserved skeleton of a full-sized adult whale!

One time, in his former life in the merchant service, Ishmael visited the kingdom of Tranque, in the Arascides islands, and met with the king, and Ishmael’s good friend, Tranquo. Ishmael was allowed to visit a preserved whale skeleton, which has been turned into a temple, and is all overgrown with plants of various types. He secretly recorded various measurements of this skeleton, much to the displeasure of the priests.

Analysis

This is one where like… you go to look up some terms that are mentioned, and you only get other people talking about this chapter from the famous novel, Moby-Dick; or, the Whale. Trying to figure out what the heck Ishmael is talking about with any of this.

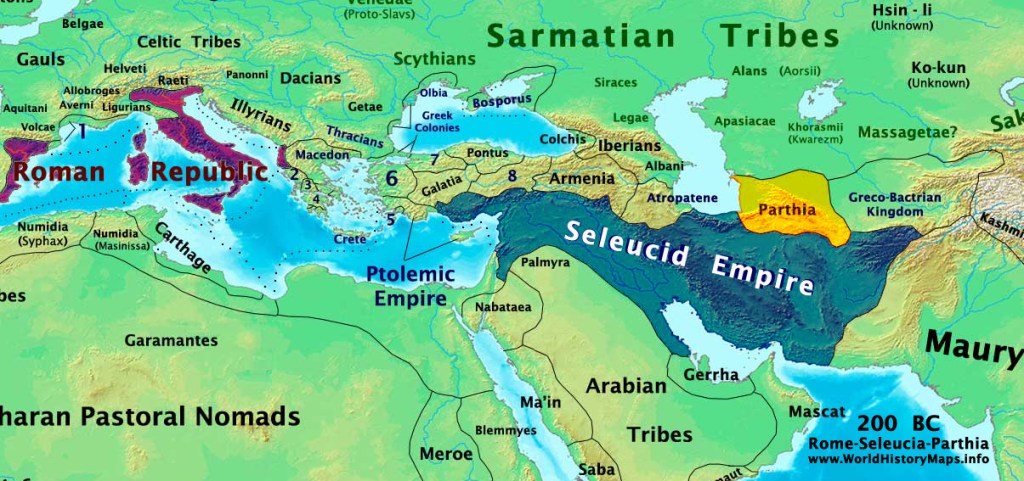

Let’s start from the top: no, you’re not a failure at geography, the Arascides are a completely made-up thing, as is the kingdom of Tranque. “Arascid” is an obscure term for the Parthian empire, which ruled what is now Iran from the 2nd century BCE to the 2nd century CE. This isn’t even a case of obscure 19th century terminology, nobody else was using these words this way, at that time.

As for what’s going on here, well… I have some ideas.

Orient, Distilled

This is basically the same sort of game being played with Queequeg, but in a slightly different way. Melville is creating a sort of pure, invented thing to work with in his fictional story. You don’t need to know the details of Tranque, it’s just a name of a place that shows up for a few pages to offer some legitimacy, that’s all. You know, those strange foreigners have their strange foreign ways, but we can still get something useful out of them! That sort of thing.

Queequeg is from an invented south seas island populated by cannibals which stands in for all such places. Similarly, this is simply a shorthand for a type of place. Purely metaphorical, here seemingly for one purpose at first (how does he know so much about whale skeletons?), but actually for a different one. One thing is the Great Weave of Life and Death (more on that later), and the other is the comparison with the Hull whaling museum.

You see, we had that story earlier in the book about the nobleman who took possession of a whale carcase that washed up on the shore of southern England. What is first presented to us as this barbaric act is later interpreted as simply another culture doing the same thing an English lord is up to in his own back yard. Once again, demonstrating the similarity of so-called civilized people with so-called barbarians, etc etc.

Except, of course, in England, it’s a tourist attraction:

Sir Clifford thinks of charging twopence for a peep at the whispering gallery in the spinal column; threepence to hear the echo in the hollow of his cerebellum; and sixpence for the unrivalled view from his forehead.

Furthermore, this serves to lend weight to Ishmael’s assertions in general. He is well-traveled, has been all over the world, seen all sorts of things. We mostly know him as the character from the early chapters of this book, a green whaler, but he has gone on to live a full and long life in the intervening years.

Shakespearean Allegory

Another fun little thing going on here, in the same vein as the comparison to the whaling museum in England, is the name of the king of this mysterious kingdom, Tranquo. When I saw that, I knew it looked very familiar… but I couldn’t quite place it, and, once again, google searches only brought up people talking about this chapter.

Then it hit me: of course! It’s a Shakespeare reference! Melville loves making those, and this is but a few small letters away from Banquo, the murdered liege lord from Macbeth. Combined, perhaps, with Trinculo, the duke Antonio’s jester from The Tempest.

Yes, I thought it was just the name of a character from that latter play, the idea of some fantastical island brought me there, I suppose. It feels like a very Shakespearean sort of story, some foreign place where the kings and towns nonetheless have very familiar names, and behave in ways that we would expect them to, per our existing notions.

The thing that’s so interesting is that Ishmael is always deeply embracing this otherness with open arms. He loves these foreign things, as he loved his dear Queequeg, back in his days on the Pequod.

The Weaver

Okay, fine, I’ve delayed enough, let’s talk about the most compelling segment of this chapter, where Ishmael is suddenly taken by one of his poetical/philosophical reveries while describing the skeleton/temple/forest scene before him.

Through the lacings of the leaves, the great sun seemed a flying shuttle weaving the unwearied verdure. Oh, busy weaver! unseen weaver!—pause!—one word!—whither flows the fabric? what palace may it deck? wherefore all these ceaseless toilings? Speak, weaver!—stay thy hand!—but one single word with thee! Nay—the shuttle flies—the figures float from forth the loom; the freshet-rushing carpet for ever slides away.

In effect, he is saying that the noise of everyday life prevents us from perceiving the truth of the world. We are all too caught up in the hustle and bustle of things to hear the words being said, deafened by the great loom that produces the things before our senses.

Very similar to other philosophical and religious musings we’ve seen in this book. The idea that there is something beyond it all, that the dead, who are now in that great beyond, have a greater perception of the truth.

[…] and by that humming, we, too, who look on the loom are deafened; and only when we escape it shall we hear the thousand voices that speak through it.

In this case, that truth is our own thoughts and deepest prayers. We cannot fully understand one another in life, and we cannot hide anything from the stillness and peace of the afterlife. When the walls of the factory come down, all shall suddenly be made clear!

It almost seems like spiritualism, some sort of dual-world theory, where spirits exist in some medium which we can interact with. But, given other things we’ve seen thus far, I think it’s a bit more vague and grand than that. It’s not something you can just put down in a few words in a book, it’s just a general idea that there is more out there, that we are only seeing some small piece of what is really going on.

Which, I suppose, since this was written in the 19th century, is literally true! There’s a lot going on that they didn’t understand, and there is yet much happening that we do not yet understand. The conflict between living life and reflecting on it and perceiving it is all throughout this book. Ishmael no longer wants to do mortal battle on the waves, he wants to reach back in time, and figure out what was really happening on his maiden voyage….

Whew! That was quite a chapter. I really wasn’t sure what I was gonna say about this one going on, besides like… “damn it sure is weird that he talked about this made up temple for a whole chapter, huh”. But, in retrospect, it’s not that weird, and in fact fits in perfectly with established themes! Go figure, this book has its reputation for a reason.

Sometimes… things are both more simple than you assume, and yet also have a fantastical and mind-boggling amount of depth at the same time. The barest outlines are easy to pick out, but once you start digging, you know you’ll never find the bottom.

I think there is an unfortunate tendency to want to reduce, to say “ah, I have figured it out, here a scheme for organizing things.” It’s a fool’s errand! Some complexities cannot, and should not be reduced, and to do so is a grave mistake.

Until next time, shipmates!

Your last paragraph sums up the chapter brilliantly. The priests feel measuring their god is disrespectful because reduces the god to numbers and diminishes the awe. The Western scientific method can kill the magic and wonder if it is reductive. Ahab being a classic Western patriarchal Uber Mensch wishes to know Moby Dick. He wants the answer, the reason for his suffering. He wants to kill and butcher Moby Dock—to reduce the whale to something his soul can master. He does not want to stand before the temple and be overwhelmed by its magnificence which will diminish him. He cannot admit what Pip learned when his ego was smashed: I am an insignicant nothing.

This chapter ties into The Mat and Line. Weaving images are everywhere in this book.

LikeLiked by 1 person