Well, I’m certainly feeling better than I was last week.

Though I wouldn’t quite say I’m no longer sick. I have a really nasty lingering cough, it’s been keeping me up all night, and freaking me out making me think I have gunk in my lungs. But, for the most part, I’m feeling a lot better. I really feel like I need a vacation, though. But I want to wait for the fall to take time off of work… when the weather is more amenable.

Summary

The four whales that were killed were all far apart, in cardinal directions from the ship. Three of them were brought back by nightfall, but the last, but the last one had to wait until morning, the murderous boat floating right alongside it. This was Ahab’s boat.

In the middle of the night, Ahab is awoken by the sharks feeding on the whale slapping the bottom of the boat with their tails. He sees the Parsee, Fedallah, crouched in the bow, watching them.

They talk briefly, and Fedallah gives Ahab three prophecies:

- Ahab will see two hearses on the sea before he dies

- One not crafted by mortal hands

- One made of American wood

- Only hemp can kill Ahab

- Fedallah go before Ahab in death

Ahab interprets these prophecies to mean that his mission will succeed, and he is effectively immortal, since they are so outlandish. In the morning, the whale is finally brought back to the ship.

Analysis

Seems a bit late in the game to introduce these prophecies, honestly. But at least two of them are things that, diegetically, Fedallah has told Ahab before. Probably before they even departed on the voyage, I would guess. Part of the latter goading on the former.

Oddly Specific Doom

Now, obviously this is another big Shakespeare reference, this time to Macbeth, with its famous extremely specific and absurd-souding prophecies.

If you’re not familiar, in the play Macbeth, the titular lord is given a prophecy by some random witches he comes across after a battle. They tell him that his king is already dead, and that he will be the new king, but that his buddy Banquo’s sons will be the kings after that. Later on, he finds the witches again, and they tell him that he won’t die until the woods come to Dunsinane (Macbeth’s castle), and that “no man of woman born” can kill him.

Of course, both of those prophecies come to pass, and Macbeth is killed. The former when his enemies cut down the trees and use them as mobile cover, and the latter when he’s stabbed by a man who was born by c-section.

That part always struck me as a bit of a cheat, and my favorite adaptation, Akira Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood, cuts it out and just goes with the tree thing. I mean, a c-section meaning you’re not somehow fully “of woman born” just seems a bit silly to me, but whatever. Could’ve just had him killed by a woman, or an animal, or a natural disaster, any number of things.

Anyway, the point being: when someone gives you extremely specific prophecies about your death, that generally means they know exactly how you’re going to die, and not that you are immortal.

In Media Res

This chapter is one of several that give the impression that there is a whole other story going on with Ahab, which we’re only getting a small part of.

In the play Macbeth, we see the initial prophesy given by the witches, but here? Ahab already knew two of these. Fedallah told him before, probably before they even left on the voyage, or perhaps merely at some earlier point, in order to steel Ahab’s conviction in his mad quest.

But we only get this one little sliver of the story. The full scope of their previous interactions are left shrouded in mystery. The grand drama of Ahab’s life is for us to imagine, not to experience in a direct way, just as Ishmael experienced it aboard the Pequod.

As I’ve said many times before, Ishmael is building the legend of Ahab, building him up in prestige and importance to mythic proportions. And so on and so forth, exalting the common, invisible worker, dealing with his trauma, etc etc. I’ve covered that.

But is this not how we experience the lives of everyone we meet? We arrive after the action has already begun, and miss many important bits. We can only truly know those little pieces of the story that we witness with our own eyes, and must extrapolate the rest.

Is that not the very nature of fiction? Speculating and creating individuals which one can truly know inside and out. Filling in the imagined gaps.

The Devil with the Details

Anyway, all that aside, I really liked the imagery around Fedallah in this chapter.

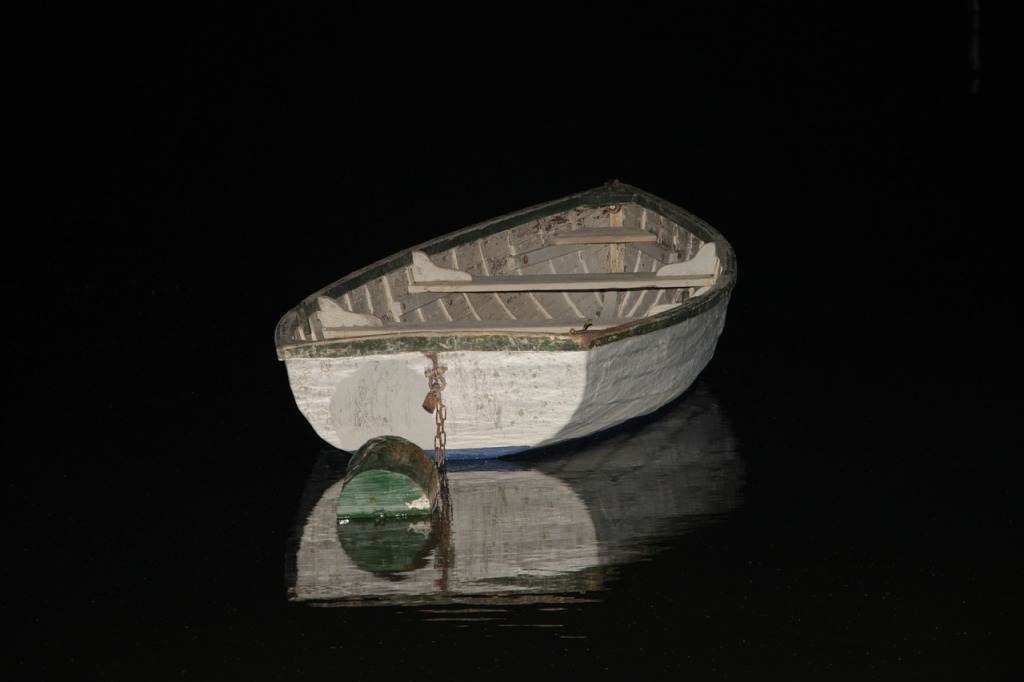

Ahab and all his boat’s crew seemed asleep but the Parsee; who crouching in the bow, sat watching the sharks, that spectrally played round the whale, and tapped the light cedar planks with their tails. A sound like the moaning in squadrons over Asphaltites of unforgiven ghosts of Gomorrah, ran shuddering through the air.

Started from his slumbers, Ahab, face to face, saw the Parsee; and hooped round by the gloom of the night they seemed the last men in a flooded world.

Here in this dark place, ravenous sharks swarming around the whales, separated only by a few inches of wood. Another great cinematic moment… which would probably be hard to realize, outside of animation or heavy CGI.

Anyway, this thing with the prophecies is tying in to the existing themes around Fedallah, tempting Ahab further down his evil (or at least sacreligious) path, and having mysterious powers tied to a more ancient pagan religion. The usual orientalist stuff, he’s allowed to have real magic because he’s an outsider, an unknown force.

It’s no real spoiler to say that Fedallah’s prophecy will, indeed, come true. This isn’t the kind of story where it drives the plot, thank god. There’s nobody rules-lawyering around trying to show Ahab some sort of hearse, or kill him with hemp in some roundabout way. No, it’s the same as Macbeth, where they only feed a feeling of invincibility, and the twist is in the way they are fulfilled, not questioning whether they will or not.

I suppose one could position Moby Dick as a sort of fantasy story, given these facts. All prophecies and legends are true. But really, the former is just the reality of being a sailor in that time, or any other, and the latter is a common literary device. Somehow, these facets have come to mostly be associated with a specific genre, in modern stories.

We like to think that the world is less mysterious nowadays. There’s nothing we don’t know, there are no mysteries that need to be papered over with myth, not in the real world. So there is a fine division in literature about the degree of speculation that is taking place. Realism, fantasy, hard and soft science fiction, and so on. Every genre has its own careful calibration of unreality that is allowed before it must be thrown out.

But in the 19th century, these things hadn’t really been nailed down yet. It’s funny how recent most of the bedrock concepts of literature are, like genre. Writing with intention, in some specific tradition, is only something that can happen when there’s a large number of people able to write. Thus, only after the invention of the printing press, and in specific material and social conditions.

People have been telling stories forever… but the shape and content of those stories shift and change over time. More eyes are upon any individual story than ever before. The world is larger and more crowded than ever, and thus we plumb yet unknown depths….

Ah, this one felt a bit aimless. I was feeling it out, y’know. This is a very evocative chapter… it has me in a reflective mood as well, I suppose. Grasping at things beyond my pay grade, so to speak.

Until next time, shipmates!